From the memoir by Hengameh Haj Hassan – Part 19

In the previous four parts of Hengameh Haj Hassan’s memoir Face to Face with the Beast, she described the harrowing conditions of the Cage—a nine-month ordeal she personally endured. This project was designed to force mass repentance from political prisoners but ultimately failed. Beginning with this installment, she recounts her observations of another form of torture, known as the Residential Unit, which drove many prisoners into psychological breakdowns. Here we also encounter the resilient spirit of women who endured unimaginable suffering yet defied the cruelty of their tormentors.

The Residential Unit: Mental Illness

Dark days lay ahead. Prisoners with mental breakdowns made life unbearable for everyone. This was a new form of psychological torture that began in quarantine. Farideh would pace back and forth, cursing at everyone—and at herself—sometimes even hitting herself. She was one of the products of the “Residential Unit.”

The method was this: a prisoner would be tortured, and the guards would stage a scene, telling her that one of her friends had betrayed her— “so-and-so informed on you, said you did this or that” (almost always a lie). The torture continued until the prisoner began to believe in the fabrication, convinced that her friend had indeed betrayed her. Then they would demand that she also denounce others in writing. Under prolonged torture, they would force “confessions” from her, which were then used to exert pressure on others. Prisoners were then confronted with one another, deepening mistrust and suspicion.

In this way, the guards created a climate of paranoia and hatred among the inmates. Prisoners became so terrified that they were afraid to even look at one another, because sometimes someone would be savagely tortured for merely admitting that another prisoner had looked at her or greeted her. Out of fear, women would spend hours sitting against the wall, avoiding all eye contact to escape the torture chamber.

Farideh became increasingly abusive, shouting and cursing constantly, shattering the nerves of everyone around her.

I first met Shahin Jalghazi in quarantine. She roared like a lion, always serious and fierce. She, too, had spent months in the Cage—I think she had been transferred there from Ward 8. Shahin was later executed during the 1988 massacre, after years of surviving torture in Evin’s punishment wards.

Shurangiz Karimian was also in quarantine. At first, I did not recognize her. Before prison, she had been a young, vibrant medical student. But now, three years later, she looked thirty years older—her eyes sunken, her back bent, one arm hanging limp at her side.

One day, “Haji” came to quarantine, as usual spewing nonsense. Suddenly he asked, “Where is the Doctor? Where’s Shouri?” And then I remembered: this frail woman was Shurangiz, the same young woman who had once visited our home. When Haji left, I asked her, “Are you Shurangiz?” She nodded with a faint smile.

Usually, those prisoners whom the regime considered especially dangerous tried to keep their distance, so others would not be punished for associating with them. Sometimes they would even warn the others: “I’m under a death sentence, it’s better not to be seen with me.”

Shurangiz had been tortured so savagely that her arm was permanently dislocated after being suspended in qapani position for days. She was now half-paralyzed, yet she still insisted on fulfilling her labor shifts—sweeping, cleaning, and carrying out chores with one arm. She never allowed anyone to take her place. She radiated a calm dignity, a composed strength that unnerved her tormentors. That was why Haji was fixated on her: despite everything, Shurangiz remained proud, defiant, unbroken. She never returned to the regular wards, always kept in punishment cells, until she was executed in the 1988 massacre.

One day, a cleric named Ansari came to quarantine, claiming: “We are here on behalf of Mr. Montazeri to investigate conditions in the prisons. Complaints have been made about unauthorized actions, which Imam [Khomeini] did not know about…” He was lying through his teeth. Khomeini himself had signed the execution orders and given free rein to his interrogators and torturers, declaring the lives, property, and dignity of the Mojahedin fair game. Yet this deceitful mullah thought he could fool us, as though we were gullible Hezbollah loyalists.

He continued: “You are all Muslims. We want to release you. All we ask is that you don’t take up arms. Even now, don’t the people insult the Imam? Does anyone arrest them? Just put down your weapons!”

One of the women—I can’t remember who—asked: “Excuse me sir, which one of us has ever had a weapon to put down?”

The cleric stammered: “Yes, yes, we know many of you don’t have such charges. We are reviewing these cases…” and went on with his sermon.

We realized then that there were internal conflicts within the regime about prison policy. After so many pointless cruelties, after months in which nearly all of us had been cut off from family visits, public outrage and family protests had mounted. The issue had become too visible, too political. The rift within the regime was beginning to show.

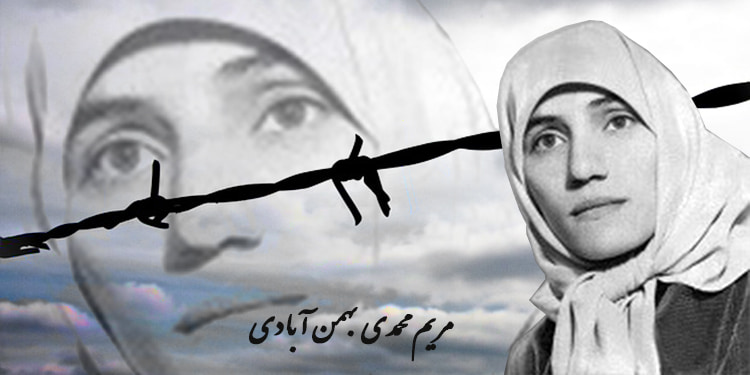

One day they called in Maryam Mohammadi Bahmanabadi. When she returned, she was beaming with joy, hugging and spinning around the other women. We asked, “What happened?” She said: “I got amnesty!”

We all cheered— “You mean you’ll be released?”

She laughed and said: “No! My life sentence was reduced to fifteen years!”

We were stunned. “That’s not something to celebrate!” we said. But Maryam explained:

“Do you really think I’m so naïve as to believe they would actually release me? No, not at all. I’m happy because this shows they were waiting for me to break, but now they’re the ones defeated. Think about the Gestapo and these other scums who expected my surrender—now their faces are slapped instead.”

Maryam, too, was executed in the 1988 massacre.

To be continued…

Shahin Jalghazi — a fellow prisoner Hengameh encountered in quarantine. Hengameh describes Shahin as fierce and protective of other inmates; Shahin was executed during the 1988 mass executions.

Shurangiz (Shourangiz Karimian) — a medical-student prisoner who, according to Hengameh, endured savage torture (including prolonged suspension that left her arm dislocated) and became semi-paralyzed but continued to work and help others despite her injuries. Hengameh reports that Shurangiz remained in punishment wards and was ultimately executed in 1988.

Maryam Mohammadi Bahmanabadi — another prisoner mentioned by Hengameh. In the memoir Maryam is briefly told she has been “amnestied” (which turned out to mean a change in sentence length rather than immediate release); Hengameh records Maryam’s defiant reaction and later notes she too was executed in 1988.

Qapāni: a form of suspension torture used in Iranian interrogation/prison settings. In practice the victim’s arms are bound so that one arm is brought over the shoulder and the other behind the back, then the wrists are locked together (often with a heavy metal cuff) and the person may be left hanging or otherwise supported in that stress position. Prolonged qapāni causes extreme, often permanent, damage to the shoulders, arms, and upper back (dislocations, nerve damage, excruciating pain), and can be life-threatening if combined with suspension. This is the technique Hengameh refers to when she describes prisoners’ arms being “out of their sockets” after prolonged hanging.