From the memoir by Hengameh Haj Hassan – Part 17

In Part 16 of Face to Face with the Beast, Hengameh Haj Hassan described her transfer into the “cage” system in Ghezelhesar Prison, a project designed by the prison authorities to break down prisoners’ resistance and force them into repentance.

In this new part, she recounts the long, suffocating days and nights inside the cage and the constant psychological torture.

⚠️ Cautionary note: The following memoir contains descriptions of torture, psychological abuse, and violence experienced by political prisoners in Iran. Reader discretion is advised.

Days and Nights in the Cage

The daily broadcast of the Quran, the call to prayer, and the news at noon—blared through loudspeakers—had one unintended benefit: I could keep track of the date and count the days. That alone was a major advantage. The rest of the time, there was nothing but silence. At first, I didn’t realize the effect this silence had, but gradually I understood: it was an effective form of torture, a constant pressure that disrupted the brain.

Nothing tormented me more than the blindfold. Why wouldn’t they just take off this damned blindfold? It cut me off completely from the outside world and forced me to retreat inward. They had deprived us of our most vital sense—sight, the main link to the outside. I told myself: without this blindfold, I could endure this place for a hundred years. But with it, my nerves were shattered.

During prayer, when we were briefly allowed to remove the blindfold, I could see the guard tower from a window. I would stare at the Pasdar[1] posted there, envious of his ability to see everything. Even in sleep, the blindfold had to remain.

The worst part was when I developed insomnia. A flood of thoughts would overwhelm me: this situation would never end; there was no way out. I was exhausted and longed for the moment I could lie down, but when it came, sleep eluded me. I tossed and turned in a dark, endless tunnel with no exit until, suddenly, dawn came again. Another day. And I thought, God, how will I survive this day in such exhaustion?

One night, suddenly, one of the girls screamed, speaking nonsense while crying and laughing. It wasn’t the first time someone had lost their mental balance. That jolted me: this was exactly what Haj Davood [2] wanted—to push us into madness through blindfolds, silence, and constant pressure. I told myself: I must sleep at night, or I’ll lose my mind too.

I was afraid of myself—afraid I wouldn’t endure, that I’d collapse, that I’d fall to my knees before the torturers and betray everything. Would I become one of those disgusting creatures who, for the sake of comfort and survival, sacrifice everyone else? God, no! Didn’t You say You never burden a soul beyond its capacity? Don’t You see I am at the limit of mine? Didn’t You promise that You are closer to us than our jugular vein? Didn’t You promise that if we call, You will answer? So help me, God! Help me!

And then, a kind of calm would wash over me. I told myself: Hengameh, you don’t want to become like those traitors, do you? Could you? No! Then be strong. Resist. Find a way to sleep at night. The enemy wants you broken and desperate to surrender. And if you give in, they won’t stop until they drag you all the way down into the swamp of betrayal and crime.

So, I decided: no more thinking, only focus on sleeping. I began counting—trees from my street, windows of our house, panes of glass, the dormitory windows from my student days, the hospital wards where I had worked. I just kept counting until, without realizing it, I fell asleep. I had defeated the insomnia.

The days were endless. To cope, I divided them into parts, especially since we were woken up so early—5 or 6 a.m.—to sit in our cages.

Sometimes, I grew exhausted from all the thinking and talking to myself. If I rested my head on my knees, I’d doze off—but the female guard would strike me on the head: “No sleeping!” Sometimes, while lost in thought, I’d suddenly be struck, my head slammed against the wall, leaving me dazed and disoriented like I’d been electrocuted.

We had to sit in such a way that our heads didn’t rise above the half-meter-high wooden planks forming the cage walls. If they did, cables, punches, and kicks from the guards would rain down on us. For taller prisoners like me, it meant constant physical strain.

Even while eating, silence was enforced. If a spoon clinked against a plate, they accused you of communicating in Morse code with the neighboring cage, and beatings followed. At every moment, we waited for an attack. The sense of danger and insecurity created permanent anxiety. Seconds stretched into hours. I wondered, God, how much longer can I endure?

I resolved that if I felt I was losing my sanity, I would kill myself. I devised a plan: to set myself on fire with the small kerosene stove used by the female guards. It was always lit, with fuel and flame.

Every day Haj Davood came to “check his machine” and taunted us: “No one will come to save you. Not even your dear Massoud.[3] Unless you yourselves decide to repent and become human beings.”

In the torturer’s twisted vocabulary, “decide for yourselves” meant surrender. And “become human” meant become an informer, a collaborator.

Each day, based on reports from the tavvabs[4] or his own plan, Haj Davood selected prisoners to be taken out, beaten, and forced to repent. Others were tortured in their cages on the spot. Sometimes he came silently, suddenly attacking one person with fists and boots.

Once, I heard a loud crack—the sickening sound of my neighbor’s skull hitting the wall—followed by Haj Davood’s furious voice screaming, “Still not human?!” Then silence. No more sound from her.

Another time, I was the target. Without warning, a massive blow to my head knocked me senseless; my vision darkened, my neck crumpled into my chest. Through the fog, I heard Haj Davood roaring as his giant fists kept crashing down.

And in that moment, I thought how merciless this enemy is, how much hatred he has for us. But strangely, with every blow, I felt more determined, more resolved.

[1] Pasdar — a member of the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), known in Persian as Sepah-e Pasdaran

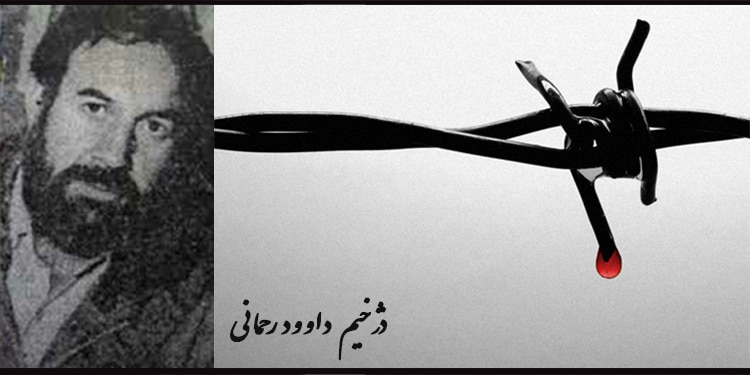

[2] Haj Davood Rahmani — the notorious warden of Ghezelhesar Prison in the early 1980s, infamous for designing the “cage” (ghafas) system, a method of psychological and physical torture.

[3] Refers to Massoud Rajavi, the leader of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK), who had himself spent years in prison under the Shah’s regime.

[4] Tavvab (literally “repenter”) — a prisoner who, under torture, agreed to collaborate with prison authorities, often acting as an informant against fellow inmates.