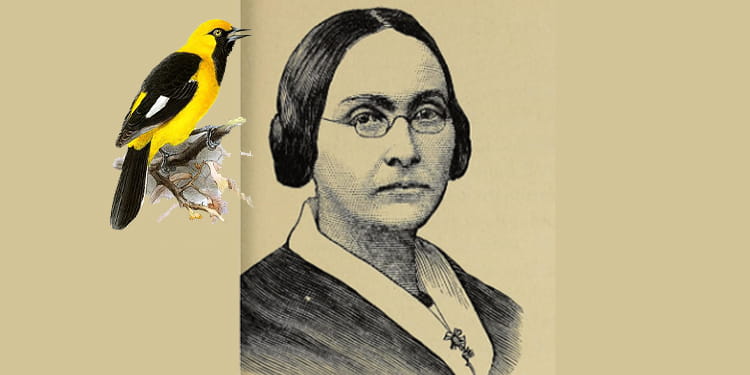

Graceanna Lewis was a rare 19th-century polymath—an artist, naturalist, educator, and abolitionist whose life bridged science and social justice. Best known for her meticulous illustrations of birds and plants, Lewis also stood firmly on the front lines of the American abolitionist movement. In an era when women were largely excluded from scientific institutions and political influence, she carved out a legacy rooted in observation, conscience, and moral courage.

Born on August 3, 1821, in West Vincent Township, Pennsylvania, Graceanna Lewis was raised in a devout Quaker family that valued education, equality, and ethical responsibility. The Quaker belief in the “Inner Light” shaped her worldview, fostering both her scientific curiosity and her lifelong commitment to human rights. From an early age, Lewis showed exceptional talent in drawing and a deep fascination with the natural world—interests that would later define her life’s work.

Lewis pursued formal education at Quaker schools and later became a teacher, combining instruction with careful study of botany and ornithology. Largely self-trained as a scientist, she developed an extraordinary ability to observe and document nature with precision. Her watercolor illustrations of birds—rendered with anatomical accuracy and artistic elegance—earned her recognition among leading naturalists of her time. She corresponded with prominent scientists, including Charles Darwin, and contributed illustrations to scientific publications, despite being barred from most professional scientific societies because of her gender.

Science, for Graceanna Lewis, was inseparable from ethics. A committed abolitionist, she used her talents in service to the anti-slavery cause. She created detailed genealogical charts illustrating the shared ancestry of all humans, visually refuting racist theories that sought to justify slavery. These charts were displayed at abolitionist meetings and lectures, transforming scientific illustration into a tool of moral argument.

Lewis was also directly involved in abolitionist activism. She participated in the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape to freedom, and remained active in reform circles throughout her life. Her Quaker convictions guided her opposition not only to slavery but also to capital punishment, war, and gender inequality.

Despite her achievements, Lewis lived much of her life on the margins of institutional recognition. Financial hardship was a constant challenge, exacerbated by her refusal to compromise her principles for patronage or popularity. Yet she persisted, continuing to teach, illustrate, and advocate well into old age.

Graceanna Lewis died on February 25, 1912, in Media, Pennsylvania. For decades, her contributions were overshadowed by those of her male contemporaries, but modern scholarship has restored her place as a pioneering figure in American science and reform.

Today, Graceanna Lewis is recognized as an early woman scientist who expanded the boundaries of both natural history and social conscience. Her life demonstrates how careful observation of the natural world can coexist with—and even strengthen commitment to justice. At the intersection of art, science, and abolition, Lewis proved that knowledge, when guided by ethics, can become a powerful force for change.