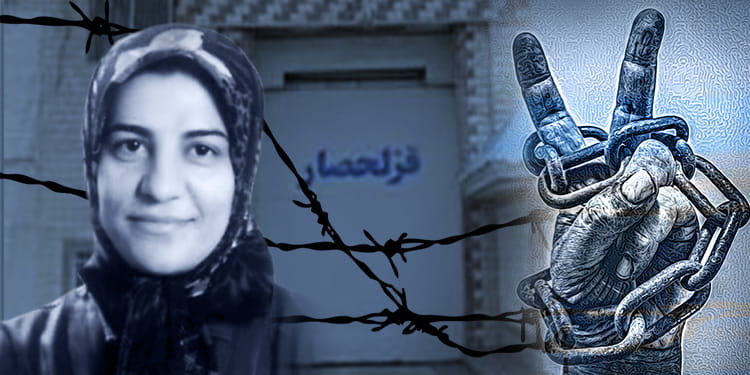

From the memoir by Hengameh Haj Hassan – Part 13

In the previous installment of Hengameh Haj Hassan’s prison memoir, Face to Face with the Beast, we read about the heartbreaking fate of young Fatemeh Moushaei, who was executed in Evin despite being only a child. In this part, Hengameh recalls forms of collective resistance inside Qezel Hesar prison, as well as the new methods of cruelty devised by the guards to break the women.

Forms of Collective Resistance

One night, very late, everyone was asleep. At that time, my sleeping spot was near the entrance door of the ward. Suddenly, I heard a voice from behind the door. I listened carefully: it was Haj Davood[1] talking to one of his “Gestapo” men.

He was scolding him:

“Shame on you! I’ve told you a thousand times, to hell with the leftists if they’re solving crosswords or reading newspapers—we already know about them! What I want is the Mojahedin’s organization! Idiot! You can’t bring me a single report about what they’re doing? Do you think they’re idle? Shame on you for being so stupid! If you stay this useless, I’ll throw you back to where you belong, you miserable fool!”

The meaning was clear: more pressure on the girls, more restrictions, fewer of the already meager “privileges.” We informed everyone in the ward. This—this network of communication—was the “organization” Haj Davood was so desperate to crush. However simple, it was our only collective defense against a regime that had absolute power over our lives. It created a shared front, a system of messaging and mutual support. And it drove Haj Davood and the guards insane. In this way, resistance continued, even behind bars.

Forms of Continuous Torture

The torturers invented new methods every day to wear us down. We, in turn, tried to resist and neutralize their tricks.

The nights were bitterly cold, and through the prison’s heating system ducts came a horrible, suffocating smoke with an unbearable stench. No matter how many times we begged for it to be turned off, they never did. We had to keep the windows open to avoid choking, which only worsened the cold. For girls with asthma, and without any access to medicine, it sometimes reached the point of suffocation and near-death.

The floor of the ward was covered with a thin, tattered carpet, full of holes, no thicker than a piece of cloth. The mosaic tiles beneath were freezing. So we had laid out army blankets across the floor. To fight the cold, we used our blankets communally: those without would be included in teams. We spread some army blankets under us and shared the better blankets—sent by families—on top. Only in this way could we sleep at all.

One night, suddenly, the guards stormed in and ordered: “Each of you, take one blanket and come out!”

We didn’t know what was happening—where were they taking us? We were pushed outside, beaten with fists and kicks, sworn at. The collaborators (traitors) strutted about like stray dogs eager to please Haj Davood, wagging their tails for approval.

After a long wait in the cold, Haj Davood himself appeared. He opened his filthy mouth and spewed his vile thoughts:

“I hear you share your blankets… doing God knows what with them! This place is the Islamic Republic’s university!”

—followed by the same obscene rants he always regurgitated. The man was foul.

He once revealed himself completely: one day, when women had been dragged out of the ward and were being beaten with whips and clubs, forced to crawl chest-down on the ground, he turned to his guards and said:

“Look at this! We used to chase after one woman… now we have so many women beneath our feet!”

That night, they left us outside until morning in the freezing cold. They confiscated all our blankets, leaving only one army blanket each, or the personal blanket sent from family.

When we returned inside, we reorganized immediately. First, to enrage the collaborators, we burst out laughing and acted cheerful. Then we announced: “Tonight, we sleep with all our belongings!”

In prison, the phrase “with all belongings” had a grim meaning: whenever guards said a prisoner was taken “with all belongings,” it meant you would never see her again—either execution or some other fate. We sometimes used the phrase in moments like this.

That night, spies didn’t understand what was going on. Quietly, we reminded each other: “All belongings.” Everyone brought out her bag, wore everything she had, and shared. Girls put on three or four pairs of socks, two or three headscarves layered, every piece of clothing available. We laughed at our own appearances, which lifted our spirits. Then, in teams of 4–5, we spread the blankets under us—because the floor was so cold—and covered ourselves only with sheets and chadors. Only the sick were given extra top blankets.

In this way, we both defeated the regime’s cruelty and protected ourselves. And the furious, helpless faces of the collaborators kept us warm.

[1] Haj Davood Rahmani (1945–2021), nicknamed “Haj Davood,” was the infamous warden of Ghezel Hesar prison during the 1980s. He had no role in the Iranian people’s anti-monarchy revolution against the Shah, but after Khomeini came to power, he joined the regime’s committees of repression. Through his ties with Assadollah Lajevardi, Tehran’s notorious prosecutor, he was appointed head of Ghezel Hesar. He became infamous for designing new torture methods, including mass isolation and psychological torture.